Good judgment comes from experience. Experience comes from bad judgment.

Unknown author

A bird hopped off a ledge and I followed. Or perhaps my life changed when I chose to finally climb those cliffs that had called to me throughout my childhood. The choices we make and the experiences we have interweave so richly that it is hard to know which is cause and which is effect.

I did not yet consider myself worthy to apply to the National Park Service. I needed to deepen my understanding and awareness, grow more sure in myself. I wanted to go “beyond.” Go way out there, so an intermediate life goal formed: return north next summer and float down the Yukon River. There was no internet, no Google Earth in the early 70’s to help me learn what this might entail but I did know that paddlewheelers had plied up and down the Yukon until highways made them obsolete in the 1950’s. Therefore, the river should be easily floatable. I ordered large scale topographic maps from the Canadian government and the USGS.

The main problem was how would I do it? I couldn’t hitchhike with a boat. In a Sears Roebuck catalog, I saw a picture of two men going through whitewater in a small inflatable raft that only weighed about 30 pounds. So I bought the Ted Williams Special, a two chamber inflatable raft that was six feet by four feet. I floated a short section of the Yakima River that I had inner-tubed before. That led to some modifications: discarding the seats and the clumsy oarlocks and replacing the paddles with something smaller and lighter. Then thinking I should try out my full gear on a multi-day trip, I decided to float the Grande Ronde River in northeastern Oregon.

I had driven along the Wallowa River, one of the Grande Ronde’s main tributaries, many times in delivering feed for my dad. I occasionally saw ranchers’ kids inner-tubing it in the summer. I also knew from years of local newspaper articles that one of the classic local outdoor adventures was fishing on a float trip down the Grand Ronde. I was able to find (in those decades before the internet days) a forest service map that showed all of the Grand Ronde except the last five miles before it joined the Snake and I couldn’t see any real danger. So one late May afternoon, Mom and Dad dropped me off beside the Wallowa River, watched me puff up my raft, put in my backpack wrapped in plastic garbage bags, and start off on a three or four day trip.

That first afternoon was glorious! The journey was as good as I imagined: bouncing and splashing along easy whitewater through a wilderness forest. Around each bend lay a new stretch with routes to choose and standing waves to go through or around. Some stretches were steep and fast, others more gentle. I didn’t see a soul. Evening brought me to a riverside campground that I had all to myself. Though water had splashed into the raft during the run, my equipment was dry within two layers of plastic garbage bags. The campground had a register with several years of comments. Most of the comments were from mid-June to late August. Almost all of the people were having a great time. Many of the people had done the run several times. The only problem seemed to be that in some years, by August, the river level had dropped to where there were lots of shallows and rocks – but that was not a problem for me in late May. All the comments deepened my confidence in the friendliness of this trip.

All night I slept to the sounds of the flowing river and I arose enthusiastic the next morning for an entire day of delightful wilderness adventure. Refreshed and ecstatic I flowed with the river. That morning the Wallowa converged with the Grande Ronde to form a bigger, stronger river. I remember one long beautiful stretch where the river ran steep, straight, and fast through the morning shadows of tall trees rising on both sides like a gothic cathedral. The far altar end of this river cathedral glowed with golden light where the river curved to the right into the sunlight.

As I came into the curve, I could see the next stretch ahead of me.

WOA!

My death lay ten seconds ahead.

A tall pine tree had recently fallen across the river. The trunk lay a foot above the river with its still-green-needled branches sticking down into the river every few feet, forming an impenetrable comb through which the river rushed. The current was sweeping me towards the branches beneath the surface where I would entangle and struggle hopelessly against the strong current until I drowned.

Let me pause, now nine seconds from the beginning of my horrible death, to more fully describe the staggering naivety of my situation. I did not have a life jacket. In a stroke of what seemed genius at the time, I figured that I could reduce the bulk of my hitchhiking outfit by not bringing a life jacket. The only reason I could imagine needing a life jacket was if I fell off my boat. So if I tied myself to my raft with a ten-foot length of rope, I would be able to use the rope to just pull myself back in. But in the instant that I saw that tree across the river, I realized I had a hangman’s noose around my waist. Even if I could make it through the straining branches, my raft would not and I’d be held hanging in the current ten feet downstream of my solidly trapped raft. Being tied to a raft caught on a tree within a swift river had never entered my mind as a possibility.

My raft was small – six feet long by four feet wide. It was not a high-pressure whitewater raft that could bounce off rocks like an inner tube. My raft was a very low pressure, blown up with my lungs, somewhat soft to the touch, two-chambered raft. There was just enough space within the four feet by two feet interior for my garbage bag-wrapped pack to lie snugly, forming, with the boat, a somewhat level, 6’x4’ soft platform that I sat cross-legged on top of.

A set of short oars had come with the raft. They were to slip through rubberized grommets that acted like oar locks but it was a clumsy configuration so I had brought just the paddle part of each oar. Imagine me holding a plastic ping-pong paddle in each hand paddling backwards and you will have an accurate image of me shooting around that bend towards the fallen tree. If you think I was really stupid to get in this situation, I will not try defending myself from your opinion. But there I was.

I am telling this cautionary story (and a few to follow) because I feel a certain moral obligation to warn any young reader who might feel inspired by my stories to go have adventures in the wild. I hope you do go have adventures. But it is amazing how stupid a college-educated kid can be. It seems like a lot of young people (especially young men) get killed out there doing naive things like I did. I felt so full of life as to be invulnerable. I was so hooked on the ecstasy of life off the leash and discovering my power to do things beyond my imagination that I did not realize how much I did not yet know. Discovering new experiences and capabilities and how to handle danger is part of the ecstasy but not knowing what one does not know is part of the danger. The ecstasy is part of the danger. All the responsible books will say to never hike alone but I have continued hiking alone throughout my life and will risk my possible death alone out there somewhere in my old age rather than give up the joys of roaming freely over the land. So I’m not sure what to say to young people exuberant with discovery except to not let it blind you to your mortality. Though you might feel like a god, you are mortal. Nature is not trying to kill you but your actions might.

Nine seconds from my death, I looked to the right to see if I could get around the tree but it spanned the entire river. I had never imagined a river could be “closed” by a tree. The full force of the current was pushing me left towards the base of the tree on the outside bank of the curve. My only chance was to go with the current and try to reach the left bank before the tree. Eight seconds from the tree, I was paddling backwards across the current with all my strength as I looked over my left shoulder trying to figure out how I would get out. The full force of the current was rushing along that bank but I scrambled ashore three seconds upstream of my death. Being tied to the boat actually helped in this instance because I could abandon ship without having to hold onto the boat. I then used my “hangman’s noose” to pull my boat up against the shore and secure it within the driving current – with the roar of the water pushing through the branches very near at hand. I lifted out my pack and carried it down past the tree. Then I went back and carried my six-foot raft over the fallen trunk.

I was ten or fifteen miles into a roadless wilderness area at the bottom of a thousand-foot deep canyon. (There are several roads into that area now.) The first road was at Troy, about 60 miles downriver. Maybe I should have found a way to hike out but I felt committed. The only way out was to continue on down. But everything was different now. Now I realized that the river might kill me at any minute.

I had known for years that snow in the mountains melts faster as the days of May and June grow longer and hotter, making the rivers rise. But that somehow never translated into an understanding that by going on this river at the end of May, I would be riding a freight train that was gathering momentum with every converging side canyon and warming hour. (When I analyze my naïveté, much of it lies in this lack of connections between things I knew; there was no awareness of implications and consequences. In the wonderful words of Jack London’s To Build a Fire: “The trouble with him was that he was without imagination. He was quick and alert in the things of life, but only in the things, and not in the significances.”) And this particular spring (1974) had the biggest snowpack since 1880 and extremely high runoff.

[A webpage on running the Grande Ronde says:

“6,000 to 10,000 cfs [cubic feet per second], high: good for experienced drift boaters and medium to large rafts. Rapids start to wash out and rocks get covered. Note: It gets a lot more swirly for paddlers in canoes and kayaks.

10,000 cfs or more, very high: medium or large rafts; experienced drift boaters. Very swirly for canoes and kayaks.”

Elsewhere, I found that the peak flow for the Grande Ronde right around when I was on it was 24,000 cfs. So I was on the river when it was more than twice as big as “very high”, twice as big as “very swirly”.]

I had absolutely no experience of how increased river flow led to increased speed and power, including the power to erode the base of a tree tall enough to drop across the entire river. Now I had to survive this experience I was having. My mind was fully awake. My only chance lay in learning everything about this river as fast as I could.

Fortunately, I had a head start. I could see the “lines” of the current. When I was four or five, my older brother and sister and I would “race” sticks down a tiny stream. If a stick got stuck, you could move it back into the main current but you had lost the time required to do that. Each stick followed a slightly different line which was always changing its speed and direction in ways unique to that line. Probably more than a thousand hours of my childhood were spent watching things float down streams so that I could project their lines and predict where they would be ten seconds later.

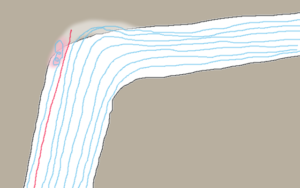

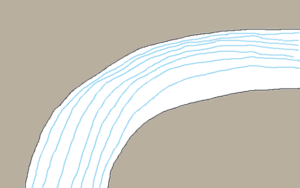

Floating on my raft was a different perspective than looking down on a floating leaf but I could easily see my line within the current and know where it was carrying me to. For example, as I floated towards a bend in the river, I could see the lines of current coming together against the outside bank of the turn. The force of the current concentrated there, leaving the current remaining along the inside bank slow and with little direction. I learned to paddle towards the inside of each bend.

Bird’s eye-view looking down on a river turning to the right.

The grey-brown are the canyon walls. The blue lines are the current.

The current lines through rapids were very easy to follow because there were no rock-filled rapids to maneuver through. The flood covered them all. Instead the lines of the current converged into a narrow chute that accelerated me into a straight, fast roller coaster series of eight to twelve standing waves. Once in them, all I could do was spin my bow back and forth to make sure I met each standing wave head-on. Because my raft was short with its weight centered, I could spin very fast with my “ping pong” paddles.

A four-foot standing wave isn’t horrific; they would have been fun in a big, eight-person whitewater raft that would plow through them. But in my little raft that crested every standing wave and plunged to the bottom of every trough, they were intense. My eyes were about three feet above the water surface so as I crested, I would stare down at a trough seven feet below my eyes and then plunge down into it and be looking right into a wave that rose a foot above my eyes. I would backpaddle two or three times as I rose up the wave to give my raft a half-second more time to summit the crest without tipping backwards. Without oarlock leverage, the only power was in my arms but their power was instantly-responsive to every swirl in the rapids. All around was the roar of the white water as I plunged and crested every five seconds. Occasionally, deep disturbing clunks rose from the floor of the flood as large, restless boulders shifted position below me. Their clunks weren’t the sharp, specific “crack” of two rocks banged together; their’s were deep underwater cracks where the sound spreads up through the water into a broad “clunk” rising up all around me. The rapids weren’t fun – too much was at stake – but they were definitely thrilling.

A four-foot standing wave isn’t horrific; they would have been fun in a big, eight-person whitewater raft that would plow through them. But in my little raft that crested every standing wave and plunged to the bottom of every trough, they were intense. My eyes were about three feet above the water surface so as I crested, I would stare down at a trough seven feet below my eyes and then plunge down into it and be looking right into a wave that rose a foot above my eyes. I would backpaddle two or three times as I rose up the wave to give my raft a half-second more time to summit the crest without tipping backwards. Without oarlock leverage, the only power was in my arms but their power was instantly-responsive to every swirl in the rapids. All around was the roar of the white water as I plunged and crested every five seconds. Occasionally, deep disturbing clunks rose from the floor of the flood as large, restless boulders shifted position below me. Their clunks weren’t the sharp, specific “crack” of two rocks banged together; their’s were deep underwater cracks where the sound spreads up through the water into a broad “clunk” rising up all around me. The rapids weren’t fun – too much was at stake – but they were definitely thrilling.

What was scary – if I had had time and energy to be scared – were the sharper river bends.

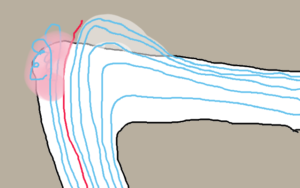

With these bends, the current went surging full-force into the facing canyon wall. As it rose up against the bedrock wall, the edges of the current’s core started to peel off to either side until only the heart of the current (the red line) reached the highest point on the wall, five to ten feet above the river, where it was crowned by a small standing wave curling back upon itself.

The downstream side of the current started peeling off downstream easily because the river was free to flow that way. Therefore, to the downstream side of the curling wave, most of the current veered into a smooth banked turn sweeping high across the canyon wall and then accelerating as it swooped back down toward the next stretch of river.

But the other side of the current that peeled off towards the upstream side had no place to go. It was confined between the outer canyon wall and the main current. That part of the current was turned back into the full force of the oncoming current sweeping up against the wall. The outer canyon wall concentrated this collision (pink area) into a boat-eating, flesh-grinding, roiling chaos kept churning by the full force of the flood sweeping past just a foot away. If I was swept into there, the only way out would probably be twenty feet straight down to the bottom of the river until I was somehow flushed out, dead, along the river bottom. (I later learned that so much air can get stirred into turbulent water that you can’t float; you just drop down through “thinner” water.)

As the current carried me towards a bend, I could see the line of current that headed to the center of the highest crest and curled back in a small breaker crowning the wave. That line (colored red) divided the downstream side of the current from the upstream side. If I was on the downstream side of that line when I crested, I would head downstream towards the next bend. If I was on the upstream side of that line when I crested, I died. I had to be on the downstream side of that “dead line”, every time.

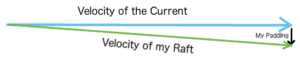

It was during these do-or-die moments that I learned the main lesson within this chapter. With my small paddles on that swollen river, I could not go wherever I wanted. The force of my paddles was so puny compared to the force of the current that I had to go where the current was carrying me. All I could try to control was my line within that current. Any paddling against the current was a waste of my energy. I needed to direct ALL my paddling energy into changing my line by paddling across the current to get onto a line that was downstream of that dead line. I was not paddling downstream. I was paddling across the current towards what would become its downstream side.

Vectors

These first two chapters contain lessons about direction which are going to deepen into the heart of what I’ve learned from that golden book. Vectors are a mathematical tool for understanding direction. Therefore, I will explain vectors in case you haven’t met them; hence this math note. Those of you comfortable with vectors can skip ahead.

A classic example of vectors is the difference between speed and velocity. The speed limit on a highway might be 60 miles per hour. It doesn’t matter which direction you are driving or whether you are going straight or going around a curve. Speed is simply how fast you are going. Speed is a number.

Velocity is speed with a direction. 60 mph to the east ends up in a very different place than 60 mph to the west. Vectors are a way to mathematically represent things like velocity. The length of the arrow represents the speed. The longer the arrow, the faster the speed. The direction of the arrow represents the direction. Therefore, the vector for velocity simultaneously expresses both its speed and its direction.

My raft was being moved by two different forces: the current and my paddling. My paddling is moving it across the current at the same time the current is sweeping me downstream. Each force can be represented by a vector. Putting the two together shows where I would end up.

The large blue arrow represents the velocity of the current. The small black arrow represents the raft’s velocity from my paddling. The green arrow shows the actual path that results from these two simultaneous forces.

The large blue arrow represents the velocity of the current. The small black arrow represents the raft’s velocity from my paddling. The green arrow shows the actual path that results from these two simultaneous forces.

The sharper the turn, the higher the current surged up the canyon wall and the more of the current got turned into a bigger upstream churn. Looking now at Google Earth (46°01’07.63″ N 117°31’36.01″ W) I count more than thirty-four, approximately 90° turns, several less than a half-mile apart, along that day’s run. There were several times when I was still on the wrong side of the deadline a few seconds away from the canyon wall, paddling with a surge of adrenaline to get across that line. before I died.

Since my backstroke was strongest and I kept my raft facing across the current, my head was facing towards the upstream side of the current. The few times I was within inches of that red deadline, I was looking straight down at boat-devouring whitewater less than a foot from the bow of my raft as the current swept me up towards the breaking wave at the top of the crest, sometimes up within inches of the canyon wall. One last adrenalin-powered paddle to hopefully keep my boat from rubbing against the rock face as my boat tilted through the banked turn, and then I spun myself forward as I swooped down from the ten-foot crest towards the next stretch of river.

Which direction was the next bend? Start paddling to its inside edge now.

Which direction was the next bend? Start paddling to its inside edge now.

The river gradually changed through the afternoon. Not only was it growing larger but it had dropped out of the forests and into semi-arid grasslands rising above the riparian vegetation. That entire day was rapids and turns and paddling. I was soaking wet. I was exhausted. But then another rapid would come and adrenalin would power more strong paddling yet again. Not until evening did I finally see a sandy beach where I could land. Without an impending crisis, I could not summon the energy to paddle to the beach. I feebly made it into the shallow water but I was too exhausted to paddle or stand. Eventually, I slowly rolled off my raft onto my hands and knees into a foot of calm water and exhaustedly crawled to the shore, trusting my hangman’s noose to pull the raft behind me. Never had my body been so exhausted. I knew I needed to eat but I lacked the energy to get my food. I sat for probably twenty minutes before I gathered enough energy to finally pull my boat ashore, unpack and eat.

The Yukon would be serene after the Grand Ronde.