If I’m not walking along streambeds, then I’m walking across slopes. I won’t feel this if I’m on a trail because trails tend to cut into the slope in order to be level across their two-foot widths. But when I am walking cross-country, I feel the actual slope of the land beneath me. I feel it in my hip sockets where the uphill thigh muscles are working harder than the downhill thigh muscles. I feel it in the sideways flex of my ankles. The slope is always there. Downhill either slopes towards my left or towards my right. This slope connects me with the streambed downslope of me and the ridges upslope of me; it positions me within the drainage system. In towns where the streams are paved over and the rain disappears down storm drains, we walk on sidewalks that are flat and orient by streets that cross, usually at right angles. But streambeds never cross. When roaming, I orient by the shape of the land.

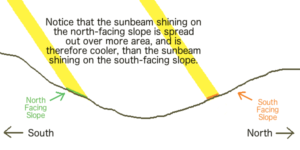

Nor is the slope felt only by my body. The land feels it, too. In the northern hemisphere, land that slopes towards the south receives more solar energy than land that slopes towards the north.

You can feel it in the temperatures as you walk across them. The direction of the slope determines which seeds will survive here and which will fail. In the desert, south slopes are baked. Plants grow more abundantly on the north slopes where temperatures are cooler and groundwater doesn’t evaporate as quickly. But in the mountains, the south-facing slopes will become snow-free sooner and have a longer and warmer growing season while the north-facing slopes might receive only a few weeks of direct sunlight each year. The steeper the slope, the more pronounced are these effects.

Challenge: In this picture of a cinder cone, what direction was the camera pointing?

Challenge: In this picture of a cinder cone, what direction was the camera pointing?

The direction of the slope (also called “exposure” or “aspect”) influences the land in so many ways that the land starts to viscerally communicate direction so that I have a sense of what direction I am heading no matter how much my route curves and swoops.

Knowing direction allows time to also be known. The sun appears due south and highest at mid-day. (Mid-day is not necessarily noon in our time-zoned, Daylight Savings Time world.) The sun rises somewhere in the east (depending on the time of year and your latitude) and appears to move to the right (when you are facing it in the non-tropical part of the Northern Hemisphere), setting the same distance to the west as it rose in the east.

It’s hard to read the clockness of this daily passage if I don’t know where the sun is in relation to south/midday. But once I do, thanks to the effects of exposure on the land, I can estimate how many hours east (before midday) or west (after midday) the sun is. Direction and time become part of the shape of the land. Knowing direction and time creates a middaycentered grid that allows each unique view throughout the day to be pieced together with approximately the same orientation.

Pace

Another trail lesson learned from much walking is to start off slower than I think I should. The exhilaration of a new day makes me impatient to get started. In the rush, I start too fast and lose my breath. I then have to back off and go through a jangly readjustment in search of my pace.

Pace is not some knowable speed at which I walk. Pace is being in balance between oxygen flowing into my inhaling lungs and arteries and carbon dioxide flowing out of my veins into my exhaling lungs. If these two flows are in balance, I can walk a long, long time. But this balance between oxygen in and carbon dioxide out is ever-changing, requiring subtle adjustments between many organs. How fast does my heart beat? How deep and often is my breathing? (Influenced by my elevation and the weight of pack) How much excess heat must be carried off through sweating? (Influenced by relative humidity and layers of clothing.) How does the exertion of the muscles help the pumping of the blood? How much blood should keep flowing along the intestines to absorb the food energy that is “burned” by the flow of oxygen? All of these systems are dancing together. If they stay harmoniously together, changing sensitively one with the other, I can walk far longer and stronger.

If I consciously start off significantly slower than my pace each morning, I begin this internal dance gently. As my breathing gradually deepens, energy grows for walking a bit faster. Unconsciously, my breathing and my pace gradually dance together and several minutes later, I realize I have found my pace and am cruising joyously. Therefore, each time I begin to walk, I try to mindfully rein in any impatience and, almost ceremonially, open with a deliberately slow amble. It’s wiser to let my body find its pace than trying to force my sense of it.

At some point, my mind gets bored with walking slower and drifts off to the land around me and my body slips into its pace. During the hike, if ever I wonder whether I am walking too fast, I slow down. I have learned to interpret the rising of this question (“Am I walking too fast?”) as a signal that I’m going too fast. If I am, indeed, walking too fast, then slowing down will allow me to settle back into my pace. If that thought was just idle wondering and my pace is fine, slowing down releases that wondering out of my mind so it doesn’t perseverate. My body will soon reset back up to its proper pace with a mind that’s free to think new thoughts.

Whenever the trail steepens, I consciously “downshift” for the haul ahead. Like a blacksmith’s bellows, my heart must pump oxygenated blood faster through my muscles and lungs so that the “flame” burning within each cell of my body can burn brighter and hotter. But there is a time lag between when my body increases its exertion and when my breathing increases to compensate. If I ignore this time lag and suddenly increase exertion significantly, the CO2 levels in my blood will rise quickly and I will start huffing and puffing – which wastes energy and dims my enjoyment. I must honor the time lag. So I slow down at the base of steeper sections, shorten my stride, giving my body time to shift gears. In that lower gear, I strive to ascend steadily, smoothly.

Maintaining my pace over changing terrain is so visceral because the connection is so immediate. When walking along a seemingly level trail, my body can immediately feel whether these steps are subtly uphill or downhill by the energy required to walk them. Any variation in uphill/downhill quickly gives feedback. With this feedback, I learn to see very subtle elevation changes in the route ahead. The route becomes more engaging because its shape determines my pace. The land shapes my breathing. “Getting a feel for the land” takes on the breathing vitality of a dance between the land and me.

Pace lessons I try to follow.

- Start off ceremonially slower than I think I should.

- Slow down (downshift) whenever the trail steepens.

- Slow down whenever I wonder if I am walking too fast.

- Slow down before I come to a stop.

Rather than stop suddenly for a rest break, I try to pick out a good place a minute or two ahead and “coast” in to my rest spot. My breathing shifts during this slow-down as every now and then a fuller exhale rises enjoyably up and out. My skin dries as less heat needs to be shed through sweating. I slow to a stop and sit in a place where I can rest and enjoy gazing out over the land.

The Third Dimension

Gregory Bateson noted how each of our eyes sees the world from a slightly different perspective and sends a slightly different vision to the brain. He points out that from the similarities and differences between those two sets of information, the brain creates a third set of information, depth perception, which resides in neither of the actual two sets.

This is a wondrous thing worth understanding deeper. Kids play with it all the time, closing one eye, then the other, alternating back and forth and watching nearby objects appear to jump back and forth in front of their background. But with both eyes open, these two points of view disappear and we see a dynamically three-dimensional world. The brain takes these two sets of information and, despite their differences, holds the two together at the same time. The similarities are given the weight of authority so that the differences are interpreted as information about the similarities – rather than the similarities being seen as only interesting illusions of two different things. The key to depth perception is focusing both eyes on the same object. You don’t really “see” it until both eyes come to focus on it – which is a combination of turning the eyes so that the object appears in the same location in both visual fields and then adjusting the lenses to bring that object into sharp focus. Then we see it residing at a specific distance from us in space.

Depth perception is an example of a powerful mental capacity: to simultaneously hold two different points of view in the mind and allow them to both be valid at the same time. When we do that, a new depth of understanding emerges that was not there before. Depth perception is not the only example of this mental capacity. Several examples of this will be described in chapters ahead. Though not all of them are visual, they all depend on this mental ability to hold different perspectives of the same “object” and simultaneously see them both as valid. I will label these examples “3D” with the yellow highlighting as shorthand for this mental synthesis process so that I won’t have to describe the process again each time.

The adjustment of the eyes necessary so that the object appears in the same location in both visual fields is important. The closer the object is, the more the eyes have to “cross”.

The closer the object, the more pronounced are the differences between what the two eyes see and the less strong are the similarities. As the object moves further away, the differences between the two views diminish until the two views are essentially similar. Beyond that, there are not enough differences to create that third set of depth perception. The distance turns into “scenery”.

But as I sit resting on a high spot, I try picking out the route I came by. Can I find the tree whose shade I sat within during my last break? My memory of that place then guides my eyes to pick out various features. There is the two-foot-thick rock ledge I had admired. Knowing that ledge is two feet high puts all that area in proper proportion. The proportions of that place have shrunken to a tiny part of my visual field but all of its features are still there in microscopic pinpricks of color for an eye sensitized by recent memory.

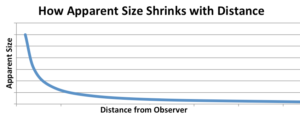

The existence of that microscopic detail surprised me initially. I assumed detail blurs out with distance. But it doesn’t (at least in clear air). The math of this shrinking is interesting. When an object is moved twice as far away, it appears only half as tall.

However, this straightforward mathematical relationship leads to this unexpected graph.

This graph is presented without numbers because the pattern applies on any scale.

This graph is presented without numbers because the pattern applies on any scale.

The apparent size of something shrinks very quickly as it starts moving away from us but then this shrinking slows down at greater distance. Th significant changes in apparent size at close range helps us gauge exactly how far away nearby objects are. This has survival value because if danger enters this nearby zone, we want to notice it and quickly gauge its distance and determine whether it is rushing towards us or not.

This nearby zone is where I concentrate most of my visual time and mental energy. I had far less experience with areas farther away because anything out there did not present immediate danger or require attention. I can’t interact with things out there; I can only look at them. I know well the pattern of how things within the nearby zone quickly shrink with distance, so I generalized my experience of quickly diminishing nearby objects out into the distance. I assumed that beyond a certain distance, all the detail just faded into a bland theater-like backdrop.

But it doesn’t. As the graph shows, the rate of shrinking quickly slows down almost to nothing. The detail is always there; it just gets packed closer and closer together. It takes concentration to pick out a relevant detail and it takes time – which I have as I sit at my rest stop. Precise vision improves with practice.

I would look out over a vast landscape as I sat resting. I had time to start practicing this pairing of a remembered perspective with what I now saw from a distance in order to create a “3D” understanding that encompasses miles, not feet. I call this Distant Vision. As I did more hikes, what I saw in the land became more richly informed. From a peak I could identify the tiny dot of green that was the cottonwood tree I had sat underneath last month, growing by the spring far out there in the desert. The green dot was easily overlooked, practically invisible to any who did not actively search for it, but once found, it brought that entire area into focus, into proper scale, connecting this place with that place. From here I could see the patterns molded into the broad land by the drainage of the streambed I had followed out to that tree. I saw that tree within its entire drainage system and better understand the tree’s place. That understanding will inform the next hike I take to that tree. And from that tree, I will be able to look back and pick out the high point that I am now sitting upon and see my current place within a bigger picture. Which then leads me to look around now. What would that bigger picture be? How much of it can I figure out now from this perspective?

Drainage patterns were some of the first patterns I noticed because the desert washes are lined with greener vegetation. Once aware of them, the drainage patterns then bring into relief all the bordering slopes which tilt towards the streambeds. The streambed and the slopes are the yin-yang forms of a drainage. They are opposites, but together they dynamically unite into the shape of the land. The more south-facing the slope’s exposure, the hotter it is. Less vegetation grows there. The colors of the mosaic of slopes start resolving into directions of slope exposure. Slopes make drainages visible. I see all the subdrainages fitting together along ridgelines like complex puzzle pieces. Paying attention to slopes reveals their relative steepness which is related to their underlying bedrock and I start to observe the intimate relationship between a drainage and its bedrock.

The farther the view, the more of our blue atmosphere I look through so the farther land appears bluer. This smooth gradient of blueing becomes another calibration of distance. When my vision is looking way out towards the horizon, I will sometimes see a sudden jump in this blueing. This reveals a horizon that lies in front of the final, uppermost horizon. That closer horizon is the ridgeline of a set of hills between the horizon and me. In rugged terrain, there are often a series of these closer horizons stepping back up towards the final horizon.

How many horizon lines can you see? I see six plus the clouds.

How many horizon lines can you see? I see six plus the clouds.

Horizon lines, drainages, slope, exposure, and bedrock geology are like camouflage. They visually disrupt the land into smaller pieces of different colors. Just as the disruptive coloration of a killdeer makes the bird “disappear” when it stops moving, so these patterns of different color disrupt and camouflage the intricate details of the unmoving land that “disappears” into scenery. But as I learn to recognize these different patterns and assign them their proper meaning, the scenery “out there” resolves into an vast land, intricately rich in every dimension, in which I can read passages of that golden book of my dream.

I am in a unique position within a small drainage with a distinctive shape and size that nests within a larger drainage with a larger shape that nests within an even larger drainage. I am hiking through a multitude of small drainages as I hike within a large, landscape-defining drainage. Drainages create an infinite variety of shapes conforming to the basic pattern of convergence. As I learn to appreciate the unique shape of each tiny drainage within a basic pattern of convergences, I become always aware of where I am. A familiarity with the terrain grows, a knowledge of how prominent landmarks will appear from different perspectives, how the larger drainages fit like puzzle pieces into a larger picture of the land. I know that over that ridge lies the drainage I hiked last month. This gives me the confidence to hike into the increasingly remote, rugged areas beyond the trails, beyond the streambeds. Each hike lays down and extends my understanding in ways that allow me to see possibilities for exploring off to the sides the next time, until the land becomes so interwoven with experiences that I am at home within it. The need for a map grows attenuated. Destinations become less important. Simply roaming the land becomes the reward.