Every time I drop something small like a nut or a screw, my eyes immediately focus on the falling item and track it until it stops and I remember my longest night. Every time, even now, more than forty years later.

The night was the Winter Solstice following my Yukon trip. Bob, my cross-country ski partner, and I had gotten an early-morning start on a new route we wanted to try. For several weeks, we had been exploring the untracked slopes that lay north of a ski area. The land rose high but gentle with lots of open meadows to roam over. Now we wanted to explore the steeper area to the south of the ski area. Our plan was to ascend the south ridge that paralleled the road, explore along it, and follow the ridge as it curved to the right back behind the ski area to the area we had explored and then ski back to the car.

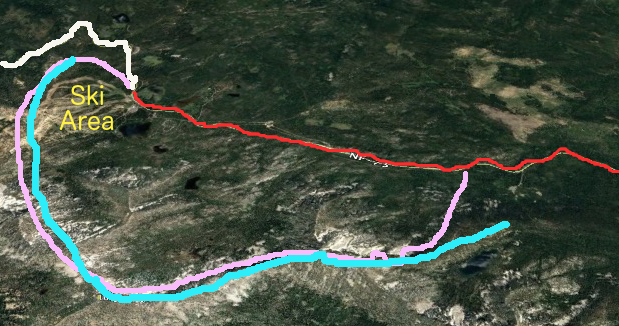

The red line is the Forest Service road that led up to the ski area. Beyond the ski area, the road was unplowed (the white line). The pink line is our intended route. The light blue line is the ridge that we planned to follow up and around to the ski area.

This left ridge turned out to be very different from the rounded ridges we had explored. This ridge was a craggy spine of rock towers surrounded by steep snowfields.

Instead of being able to ski along the crest, the snarly top kept forcing us into contouring along the steep left flanks so that we were unable to look down on the right side towards the ski area. Not until afternoon was waning were we able to cross back over the ridgeline to start our descent. That slope was too steep to ski so we took off our skis and trudged down the slope. As we went down, the cable binding came off my right ski and slid down the slope ahead of me. I laughed, because it was all part of the adventure and I was young, invincible, immortal. I knew I would find it at the bottom of the slope because gravity works in a predictable way.

But we didn’t find it at the bottom and that created a problem because that binding held my foot onto the ski. Without the binding, I was connected to only one ski in deep unpacked snow. We fixed that by tying my unconnected foot to its ski with some nylon rope. The rope around the bottom of the ski prevented it from gliding, so I could not do a natural stride, but the resulting shuffle was all right because we were just following the short slope back down to the road.

Except we didn’t get to the road. We kept following the slope down through a series of snow-filled meadows and forests as the shortest day of the year faded into the dusky beginning of the fifteen hours of the longest night of the year and still we had not come to the road. In growing confusion and darkness, we finally came upon a wide-open path that suggested a snow-covered Forest Service road contouring through the forest. The ski area must be to the right we thought, so we started following the open line through the woods in that direction. Night darkened but the darkness of a snow-filled forest is brighter than familiar darkness. It has distance and rounded softness, filled with a silence muffled by the snow.

Eventually we came upon a sign barely sticking above the snow that said the ski area was fourteen more miles. We had no idea how that could have happened. We had been skiing all day, probably ten miles of mountain skiing and now I faced fourteen miles of shuffling through the longest night. We stopped to rest and tried to build a fire on a branch platform like some books we had read suggested, but we could not pull it off and so decided to keep skiing and make it back to the ski area. There was no wind within the still forest, but the temperature was gently dropping to ten degrees. We had to push through several inches of soft powder snow with each stride so Bob broke trail. I was unable to push with my right, tied-on foot. This created an unnatural stride which gradually, thousands of strides upon thousands of strides, strained my muscles around my right hip joint that can still be slightly felt forty years later. Every few hours the cord around my foot frayed from the snow crystals and had to be replaced. The half moon set as on we went into the darkest part of the snowy night, a dark gray road within black trees. Distances could not be seen, so there was no sense of progress through a landscape. We crawled along a slow treadmill that sometimes rose, sometimes descended, sometimes curved but was always fixed in a limbo of darkness.

But it was the longest night of the year and at some point, probably around three in the morning, still hours from dawn, I slid into a sleep cycle that I couldn’t push through. When we stopped for a break, I used my pack as a pillow and lay sideways in the snow to take a short nap. Bob wouldn’t let me. I told him that it would be just a short one and there was no need to worry. I wasn’t tired; I was just sleepy, and a short nap would rejuvenate me and then we could keep going. But he wouldn’t let me. He insisted we keep going (Thank you, Bob.) so up I got and resumed shuffling step after step within the unmoving perpetual dimness of an exhausted mind within a long, long night.

Eventually, the night grew less dark. We went around yet another long, slow cresting curve and in the just-beginning-to-brighten pre-dawn dimness, we recognized a curve in the road about a mile before the ski area. We knew then that we were going to make it. Bob skied ahead to find someone and rustle up some hot chocolate or tea for us while I shuffled slowly along. But I had to keep stopping because the pre-dawn sky was filling with the most beautiful light I had ever seen. Fading night-dark blues and strengthening salmon yellows. Streaks of high cirrus clouds hinted at pinks. The light was so enchantingly beautiful, I had to stop and drink it in for several minutes. Then I’d shuffle on. The light gradually strengthened into golden sky and faint pinks on the thin clouds and mountain ridges. An onlooker would probably see me as an exhausted man with only enough strength to shuffle ten or twenty feet before needing to rest again. But that was not what was going on. Yes, I was exhausted, but not that exhausted. I had skied all night and I could probably ski another hour or two if need be. But the light. I had to stop every few minutes to take in its new level of beauty. The light was all around me, flowing into me, filling me, nourishing me more profoundly than food or drink. There, beyond exhaustion, the light was all I needed to make it another ten or twenty strides. Sunrise was approaching; the light grew ever more beautiful, demanding that I stop more and more just to honor its beauty.

That longest night changed me in three ways. The first goes back to when my cable binding fell off and slid down the slope. Instead of tracking it like a hawk, I laughed like an immortal god at the adventure of it all, knowing that I would find it at the foot of the slope. But I didn’t find it and I paid a price for my casualness which included superficial frostbite in the foot that had to be tied to the ski. Ever since that night, every time I drop something, my eyes immediately focus on the falling item and track it until it stops. I have no memory of creating this new response to a dropped item. The change must have been sub-conscious, sudden and irrevocable. My subconscious made a unilateral decision: “I am never letting you in your “so sure of yourself” way make that stupid mistake again. Ever.” The change has been permanent. And every single time I drop something like a screw, I track it until it stops and as I do, I remember that night.

The second change was a dawning awareness of the importance of divides. I was very confused as to how we went so wrong. For years I tried to figure out what happened. As I grew more knowledgeable about the shape of the land, I developed a hypothesis and when Google Earth came along, I was able to confirm it.

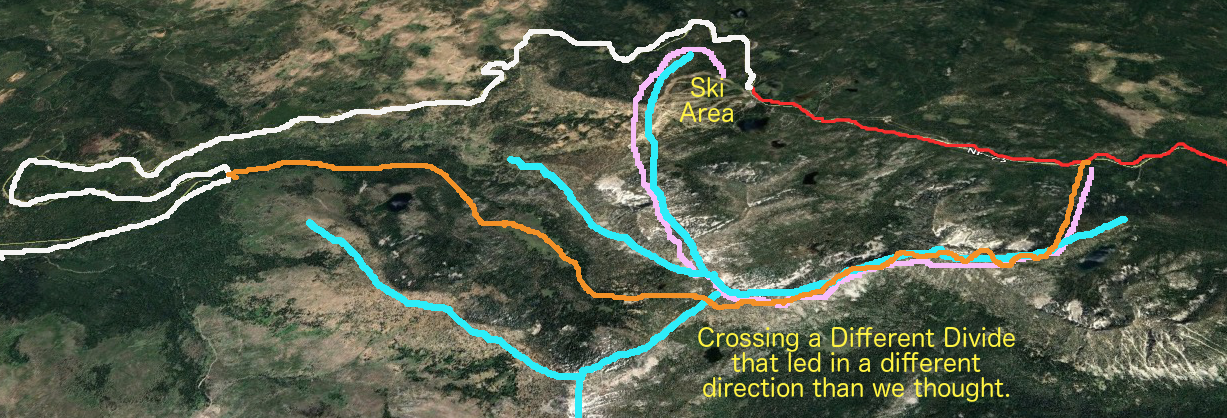

The red line is the Forest Service road that led up to the ski area. Beyond the ski area, it was unplowed (the white line). The pink line is our intended route. The light blue lines are the system of ridges in this area. The orange line is how we went over a different divide that led us off on a different direction until we came to the white line and skied the unplowed road back.

What we had assumed was a long, single ridge (because that is all we could see from the road) actually forked into three ridges near the highest point on the ridge. But we weren’t aware of the fork because we had gone by it as we were contouring along the left flank. When we finally crested the ridge again for our descent, we were looking down into a drainage that led away from the ski area with a whole other divide separating that area from the ski area. It took the road we eventually reached fourteen miles to snake its way around and back to the ski area.

Ridges divide. What actually lies on the other side? Some divides are dramatically obvious while others are deviously subtle. Be mindful whenever you cross a divide. Their two sides often lead in very different directions. Divides are an important phrase that occurs in that golden book of my dream as major definers of the land’s shape, determining the direction things flow upon it.

But the most important life changer of that night was being opened to the beauty of light. Ever since, in my roamings, I often just stop and gaze at the light glowing around me, content, deeply nourished by what I have come to call the Enoughness.

A possible explanation is that I was too exhausted that night to filter and sort my visual input in our usual way. The part of my mind that organized visual input into “mountain”, “cloud”, “tree” had fallen into an exhausted “sleep” and now I was seeing the light in its full glory, with less interpretation, less cerebral filtering. Or maybe, after straining through the dark of the longest night with no artificial light, with just hours after hours of starlight on snow, my retinas’ light-starved cones, maximally full of stored-up, color-detecting chemicals, were fully absorbing every subtle tint and glowing hue that flooded my brain with hope as the Earth turned the sky and clouds above me and the mountains and snow around me, turned us all towards the warming, life-sustaining light. That morning so opened me to the beauty of the light that its simple “enoughness” has filled my life ever since with an economic calm. I know I don’t really need much because the beautiful light of this world is enough.

A few months later, I returned home from another ski trip with Bob. Dad said that Big Bend National Park had called about hiring me as a seasonal naturalist. My dad was a salesman and after he answered the ranger’s questions, he said, “Now, let me tell you about my son” and proceeded to sell me. (A year later, I had a chance to look through my personnel file and there was a note the ranger had made during that call. “Father most enthusiastic.” Thanks, Dad.) I bought my first car, a subcompact, that easily held my backpacking equipment, some clothes, and extra basic cooking equipment my family gave me, and headed down to Texas to become a National Park ranger. I was on my way!