My Metaphysics

About 1 ½ years ago, I realized that the book I’ve been trying to write had to include “my metaphysics.” For the last six Cairns, I’ve intended to have an article that addresses at least some of this but when I tried to write it, I got bogged down for a variety of reasons and kept opting to postpone it to the next issue. But I took a vow after Cairns #82 that Cairns #83 would include my metaphysics, no matter what shape the writing was in. It continues to challenge me, hence the two month delay with this issue but here is where I am in my writing at this point. Many sentences could be expanded into paragraphs and all the pieces don’t quite fit but hopefully you will find a narrative line through a 27 page essay. I would appreciate your constructive feedback to help me better express (or lay to rest) these persistent thoughts.

Graphs

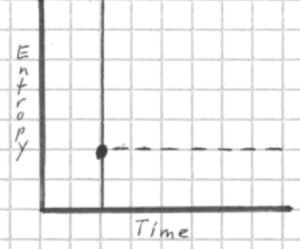

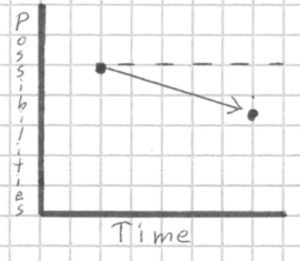

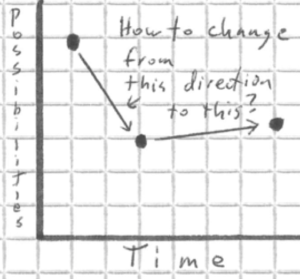

Start with this graph concerning the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The dot represents a defined system’s total overall entropy at a specific time. (Entropy is a measure of what portion of a system’s energy is unavailable to do useful work. The First Law of Thermodynamics states that energy is neither created nor destroyed but the Second Law states that the ability of energy to perform work gradually declines as some of it is “leaking” into the random molecular vibration of heat.) By defined system, I mean closed to any inflow from beyond it. One of the implications of the Second Law is that the entropy within such a closed system can not decrease.

Start with this graph concerning the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The dot represents a defined system’s total overall entropy at a specific time. (Entropy is a measure of what portion of a system’s energy is unavailable to do useful work. The First Law of Thermodynamics states that energy is neither created nor destroyed but the Second Law states that the ability of energy to perform work gradually declines as some of it is “leaking” into the random molecular vibration of heat.) By defined system, I mean closed to any inflow from beyond it. One of the implications of the Second Law is that the entropy within such a closed system can not decrease.

The solid vertical line through the dot with shading to the left of that line shows that the system can only move forward, to the right, through time. It can’t move back. It can’t stop and mark time for awhile. The only possible movement is ahead. And when the system gets to that future point, the only movement then will be ahead even more. Time can’t stop. The defined system will always be moving “forward” through time.

The dotted horizontal line with shading beneath it shows that entropy within this defined close system can not decrease. It can remain steady, moving neither up nor down so this dotted line is different than the solid vertical line. That solid line meant that remaining steady is not a possibility. Time must proceed. Entropy, however can theoretically remain steady (hence the dotted line) but in actuality, it always increases. Closed systems run down. Therefore any dot representing this defined close system in the future must lie somewhere in the unshaded space bounded by the two lines through the first dot.

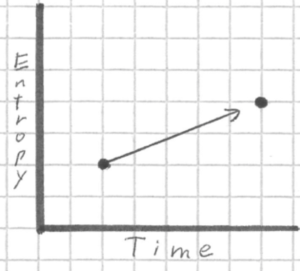

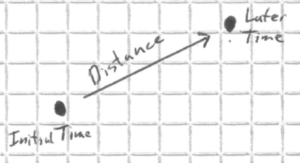

This leads to the second graph with a second dot which represents the same defined system later in time. (For simplicity, I removed the two lines through the first dot but those constraints will always apply.) This creates an arrow (vector) from the first dot to the second. This arrow expresses one of the implications of the Second Law of Thermodynamics: in a closed system, the entropy will increase over time. The system is “doomed” to “run down.”

This leads to the second graph with a second dot which represents the same defined system later in time. (For simplicity, I removed the two lines through the first dot but those constraints will always apply.) This creates an arrow (vector) from the first dot to the second. This arrow expresses one of the implications of the Second Law of Thermodynamics: in a closed system, the entropy will increase over time. The system is “doomed” to “run down.”

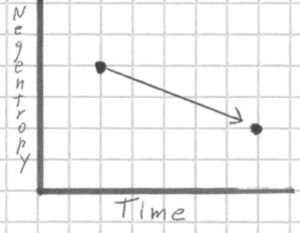

However, because an arrow pointing upward does not graphically match our sense of “running down”, we change our y-axis from “entropy” to “negentropy” which is “negative entropy” or free energy, the opposite of entropy. This changes the graph by flipping everything upside down so that now, the dot’s movement through time slides down, fitting with our sense of things running down.

However, because an arrow pointing upward does not graphically match our sense of “running down”, we change our y-axis from “entropy” to “negentropy” which is “negative entropy” or free energy, the opposite of entropy. This changes the graph by flipping everything upside down so that now, the dot’s movement through time slides down, fitting with our sense of things running down.

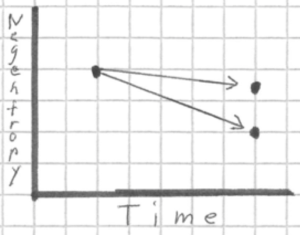

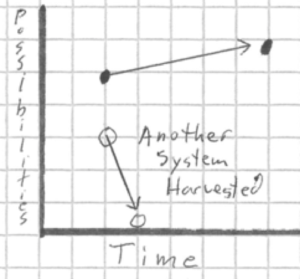

Next, we add another dot at the same future point in time, creating two possible arrows extending into the future. This illustrates that the Second Law does not specify how quickly a closed system must run down. (Theoretically, it can hold steady forever.) The decomposition of a desert bone can be extremely slow while a detonated bomb is explosively fast. The closed system can move downhill at different rates.

Next, we add another dot at the same future point in time, creating two possible arrows extending into the future. This illustrates that the Second Law does not specify how quickly a closed system must run down. (Theoretically, it can hold steady forever.) The decomposition of a desert bone can be extremely slow while a detonated bomb is explosively fast. The closed system can move downhill at different rates.

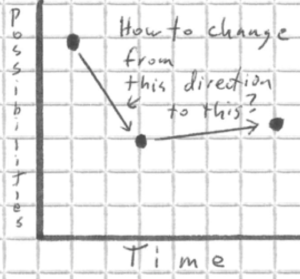

Then I make the first “stretch” that leads me to think of this as “metaphysics”; I change the y-axis from “negentropy” (a precise concept, capable of being measured in specific situations) to the very loose but poetically more suggestive concept of “possibilities”.

My image for this phrase is two skiers high in the mountains stopping to pick out a beautiful route of descent. One skier is higher on the slope than the other. The lower skier has many routes down available to him. However, the higher one has more possible routes than the lower person because one of her many routes is to descend down to the other skier and accessing all the routes the other skier had. But she also has available all the additional routes branching out on all the routes angling across the slope above the routes of the lower skier. She has more possibilities because she is higher on the slope. This image of how many possible paths lie open to a system is what I mean by “possibilities”.

This is the graph that underlines what I think of as the heart of the Second Law. Energy, the ability to create change, is flowing towards less possibilities. The universe flows in a direction, just like a river. Upstream lies in the past and downstream lies in the future.

This is the graph that underlines what I think of as the heart of the Second Law. Energy, the ability to create change, is flowing towards less possibilities. The universe flows in a direction, just like a river. Upstream lies in the past and downstream lies in the future.

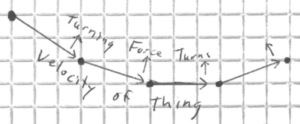

In physics, if an object changes position, it has a velocity (the change in position divided by the change in time required for that change). This velocity has both a rate (the speed) and a direction to it. In the second “stretch” of my metaphysics, I will be thinking of this change between the two dots on our graphs as defining a “thermodynamic velocity” and thinking about that system in terms of the mathematics of velocity, acceleration, and force. The bone decomposing in the desert, for example, has a very low thermodynamic velocity downwards while a detonated bomb has an explosively large thermodynamic velocity downwards.

Everything, if isolated within a closed system, will flow down to thermodynamic equilibrium. Without evaporation from the sun, all fresh water would gradually return back to the sea (or other land-locked basins). Without winds from the Sun’s differential heating of our globe, ocean waves would quiet into a globe-spanning mirror of smooth water before freezing over. Life would fade out.

Open Systems

But this is not happening. We live within an open system. Yes, things are flowing down like a river but also, like in the water cycle, solar energy entering our system is evaporating fresh water from the sea and moving it back over the continents. The Second Law still applies, still strongly shapes the structures of life, but it does not prevent life and other enterprises from creating possibilities within the Earth’s open system. The only constraint is that whatever is built up has to be thermodynamically less than the amount of solar energy that flowed through the system to create it. Change can not be 100% perfectly efficient. Some of the possibility-creating energy has to end up as heat (random vibrations in the surrounding molecules).

Flows that are open to outside energy can become cycles. The Second Law defines the direction towards which things will spontaneously flow but incoming energy can do the work of lifting some of that material back “up” where it can flow “down” again. The water cycle is driven by energy flowing from the Sun and fresh water becomes possible. The rock cycle is driven by the heat energy flowing from the center of the Earth and dry land becomes possible. Cycles become the flowing foundations from which many possibilities emerge.

The constant challenge every living thing faces is to find a way to “swim upstream” in order to maintain its position within this thermodynamic flow. Can a warm-blooded creature, for example, maintain its internal temperature within the downward flow of energy as the chemical energy within its food becomes metabolic heat that flows away into the cooler air around it? Our lives are a series of temporary solutions to energy loss, putting on insulating clothes, eating more food, lighting a fire. If we run out of temporary solutions, we will cool down to death.

How does life solve this constant need to swim upstream against the flow of entropy? Every introductory biology textbook asks this question and then gives the same reply. Living things survive by harvesting sources of energy around them. Plants harvest sunlight. Herbivores harvest plants. Predators harvest prey. Decomposers harvest carcasses. Through harvesting, upstream is possible.

It’s like a roller-coaster. The Second Law does not prohibit a roller coaster from coasting uphill. It just requires that the coasting up has to be preceded by a larger rolling down. The up by itself is not possible but the two together as a down powering a smaller up is possible.

It’s like a roller-coaster. The Second Law does not prohibit a roller coaster from coasting uphill. It just requires that the coasting up has to be preceded by a larger rolling down. The up by itself is not possible but the two together as a down powering a smaller up is possible.

The image of this reality, for me, will always be the dead deer I watched over the months as it turned from a freshly-mountain lion-killed intact body to a few brown bones and leather. An orgy of blowflies gathered within hours and then gradually dispersed over a couple of days, followed by the bursting forth of their seething maggot children. Soft parts of the deer transformed into maggots which, as they grew, became food for rove beetles and other maggot predators. Mature maggots wiggled away from the carcass and dug themselves into the ground to pupate and emerge as adult flies, setting forth to hopefully cross paths in the future with another freshly-dead carcass. Near the end, all that remained of the original deer was hide, hairs in the soil, and scattered bones. A variety of insects, few in number, occasionally showed up in some restrictive, specialized part of the carcass for a while and then moved on.

The deer ate the desert plants. The maggots ate the deer. The rove beetles ate the maggots and little remains. Like a roller coaster, each transfer of possibilities “up” required first a greater “down” of animals consumed. This is the reality of our existence. We must harvest the possibilities of others in order to maintain and grow the possibilities within ourselves – all the while doing our best to remain unharvested by others. Each of us is a subsystem of a much larger, planetary open system. Incoming solar energy allows plants to create biochemical energy possibilities which then are harvested over and over again through food chains from producers through decomposers. This is the structure we live within.

Structures Create Behaviors

One of the great insights of systems thinking is that structures create behavior. Many times, behavior that we might find fault with arises, not because of some fault in the people involved, but because of the kind of structure they are involved in. People within that structure will tend to behave in that way.

Here is an example I use with my eighth graders to help them understand this idea. If we are walking back to the bus at the end of field study and a teacher is not at the front of the group, there will almost always be a stampede of running children near the end of the walk back which can grow “mindless” enough to be dangerous. It doesn’t matter who the kids are; the dynamics are created by the situation.

The situation is that the “back seat of the bus” is valuable real estate to kids. Of all the rows of seats on the bus, there is only one that is “the back”. Other ones can be “near” the back but only one row is “at the back”, furthest from the bus driver and the adult world. So it is cool to be sitting in the back seat. The first people in line at the bus are the first people to get on the bus and are therefore the people who can sit at the back of the bus. So when we get close enough to see the bus, some of the kids start to walk a little faster. This moves them past the other kids towards the front. These kids, being passed, become aware that those faster kids are making a move to be first in line back at the bus so these passed kids speed up, which leads the other kids to speed up which leads other kids speed up. This can escalate amazingly fast from a walk into a full-speed stampede. I’ve seen it happen enough times to know that the stampede is not because a couple of the kids had “bad behavior”. It’s just the structure they are operating within.

Systems thinkers say that if you don’t like the behavior that arises within a structure, then change the structure rather than trying to change the behavior. Many teachers stay in front of their class for this reason. But I want kids to be leaders, not followers. So I have a banner that’s held by the group leader (a position that kids rotate through over the course of the field study) and no one gets in front of the group leader. If you don’t like the behavior that consistently arises within a situation, change the structure of that situation.

Gradient of Wealth

Having said that, we now have to see how certain structures have arisen in response to the Second Law of Thermodynamics. To remain alive and reproduce within a universe shaped by the Second Law, one must harvest other subsystems while avoiding being harvested oneself. Our species has been able to satisfy this requirement spectacularly. One of our main tools for doing this has been the creation of a money system that allows us to convert things that are not directly necessary to our survival into something that can be sold for money that can then be used to obtain something that is necessary. Furthermore, we have created ways to let money accumulate so that it can be stored up for the future. Many animals will lay up food supplies or fat reserves to make it through a winter but we can accumulate far more money than we will ever need within this year to be banked against future years. This allows our economic activity to grow beyond “mere survival”. Building a church or playing golf or restoring old cars become possibilities.

If you have more money than is necessary for survival, you can use some of that money to, in some way, raise yourself above the crowd. For example, the top of a hill has a better view but less space than the bottom of the hill. Therefore, through supply and demand, the top of the hill will become more valuable real estate than the bottom of the hill. People with the extra money to be able to pay this higher price will, literally, look down on the people around them while those people down there will be looking up to you. But the next hill over is a bit higher so wouldn’t it be nicer to have bought there instead? Nicer view and it will be apparent to all that you have more wealth than almost everybody else, even more than the people on the top of the shorter hill over there.

The tool of money allows a structure to grow that I call “the gradient of wealth”. This is like the initial kid starting to walk a bit faster in order to be at the front of the line to get on the bus. You want to be seen as having more money than those around you but, as you move up the gradient of wealth and leave some behind, you find that more of the people who are still around you are trying to get in front of you, wanting to be the one who owns the house on the top of the highest hill. They are motivated by the same zeal and have absorbed similar value systems of what brand of clothes and cars and alcohol are higher on the hill than other brands. A 28 foot boat is bigger than a 21 foot boat. As one moves up the gradient of wealth, the things you buy become more expensive. It costs more the higher up one moves. That’s where the gradient of wealth gets tricky. One can never get to the top; it extends upwards for billions and billions of dollars. But as one strives to position oneself higher than others upon the gradient, the more one is surrounded by people striving to position themselves higher than others upon the gradient of wealth, measuring their position in terms of increasingly more expensive items. Therefore, one’s wealth does not necessarily secure a sense of “enough”.

The higher people move, the more people’s income will come from investments made with the wealth they have already accumulated. Therefore, if a person wants to keep moving higher within the gradient, it’s necessary for their wealth to generate a higher rate of return than the invested wealth of those around them. So there is a push for higher rate of return, higher rate of return.

If you are smart enough to develop an investment that generates a higher rate of return, you can manage the money of others and take as commission a percentage of that higher rate of return. So the gradient of wealth nourishes lots of smart people looking for ways to generate a higher rate of return.

The main way to generate a higher rate of return is to externalize costs and internalize profits. Almost by definition, this means that you benefit at the expense of someone else – in the same way that the blowflies benefit at the deer’s expense and the rove beetles benefit at the maggots’ expense. Therefore, some of your investment will probably intrude into areas that others will object to as being wrong. So you need power to counter this moral resistance. Getting lawmakers elected who will write laws that make your high rate investments legal becomes a good investment. “A million spent here on these politicians allows me to make ten million over there. Good rate of return.”

Unfortunately, striving for the highest rate of return leads to harvesting other systems faster than they can sustain themselves. The soil erodes. The fisheries collapses. The savings of a life’s work in a pension is looted by those who did not do the work. The term “citizen” is degraded to “consumer.” More and more people feel disenfranchised. The military becomes more “mercenary” in the sense of poor people enlisting to get access to opportunity – rather than fighting for what is right. A shared sense of national unity fades. One’s wealth might increases but at the expense of the wealth within the world. But that’s the way it works because of the Second Law. One can only maintain one’s position by harvesting others. It’s harvest or be harvested. In this stampede for the best seat in the bus, one orients by one’s position within the group and loses touch with the world beyond that, like a kid so intent on the back of the bus that they run blindly into the street. In both cases, kids striving for the back and adults striving for wealth, systems theorists would say that the problems that arise are not because of a malicious intent of the people but in the dynamics of the structures they live within. The solution to the problem lies in changing the structure.

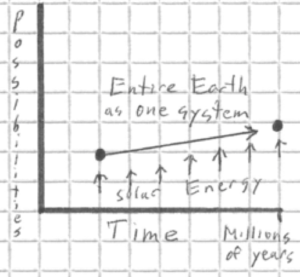

Gaia

A watershed moment for me was reading James Lovelock’s book, The Gaia Hypothesis. He is an atmospheric chemist who was contracted by NASA to help develop instruments for detecting life on Mars. What chemical processes might reveal the presence of life? He concluded that there was no need to go to Mars in search of life; we can already tell from Earth there will be no life because the Martian atmosphere is at thermodynamic equilibrium. There are no processes that are using incoming solar energy to cycle some of the planet’s gases back up to a higher energy state.

Earth’s atmosphere, on the other hand, is dramatically far from thermodynamic equilibrium. The best example: the atmospheric oxygen that makes up 21% of our atmosphere. Oxygen is highly reactive, sometimes explosively so, and will oxidize many things. Atmospheric oxygen is constantly being drawn out of the atmosphere. It will only remain in the atmosphere if there is a process (photosynthesis) that is cycling it back fast enough to maintain it in dynamic equilibrium.

The Earth is not at thermodynamic equilibrium which means that, after many billion years, life has actually moved the entire planetary system “upstream”.

How is this possible? Since the Earth is an open system, open to solar energy, this is theoretically possible. There is no violation of the Second Law involved. But how does this entire planetary uplift actually happen? What lessons can we learn to help us turn the direction of our planet’s thermodynamic velocity up- wards? That is the question underlying the rest of this essay.

How is this possible? Since the Earth is an open system, open to solar energy, this is theoretically possible. There is no violation of the Second Law involved. But how does this entire planetary uplift actually happen? What lessons can we learn to help us turn the direction of our planet’s thermodynamic velocity up- wards? That is the question underlying the rest of this essay.

How do we change the downward direction of our planet’s thermodynamic velocity upwards?

The water cycle is the major illustrator of this for me. I have written about this over the years so I will only briefly sketch it here. 90% of the water that evaporates from the ocean falls back onto the ocean before it ever reaches the land because it takes a lot of energy to move water through the atmosphere. The annual amount of rain that reaches land from the sea is only around 11 inches of rain, barely enough to sustain a desert grassland. But some of this rain that falls upon the land is transpired by plants back into the atmosphere where it can fall as rain again. The gift of fresh water from the sea is recycled almost two times before flowing back to the sea, so that around 29 inches of rain on average falls per year, enough to sustain forests.

Photosynthesis requires water. This recycling of rain allows plants to conduct more photosynthesis which creates more plant surface area. This has multiple effects. (1) It leads to additional transpiration and photosynthesis. (2) This makes more biochemical energy available within the biosphere, increasing the amount of life that can be supported. (3) This increased vegetative growth slows down the rock cycle. More plants cushion the ground from the pounding rain. More roots cling and hold soil particles against erosive forces. More plant materials decompose to enrich the soil. As the soil part of the rock cycle slows down, the flow backs up. Soil grows “deeper”, capable of nourishing more plants and holding more rain so that more of the rain can be recycled back. This flow of intertwining cause and effect between rain, soil, plants, oxygen, and solar energy forms a positive feedback spiral that I have come to call an Upward Spiral.

“Ecological services” is a phrase that refers to all the activities that various species have evolved to contribute to these upward spirals. They harvest energy from the greater system but they then use that energy to do the work of altering flows so that even more energy from the sun accumulates within the greater system, creating more possibilities. The textbook explanation for how life can exist within a universe shaped by the Second Law explains how individuals can sustain themselves by harvesting others. But the full answer is larger than that. What work do we do with the possibilities we harvest from others? Salmon transport nutrients from the sea back up to the forests in the headwaters. Earthworms aerate the soil so that soil-forming process can occur at greater rates. Beaver retard the mountains’ spring meltoff with leaky dams that reduce the erosive surge and maintain a more even flow longer into the summer growing season. Though they are harvesting some of the possibilities from the subsystems around them, they are then using that harvested energy to do work that changes rates of flows so that more opportunities for plants to grow more surface area that can absorb more of the sun’s energy into the biosphere.

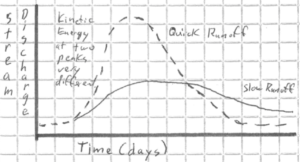

My life brought me into a sandstone canyon that had once had aspen but now was gashed with a massive arroyo. This gully contributed to a downward spiral that was draining possibilities from the canyon. It provided a much faster route out of the canyon for groundwater that had been percolating slowly through sand so that groundwater diminished. Less groundwater fuels less photosynthesis. Plant cover diminishes which removes some of the soil’s protection from summer sun and pounding rain. Less of the rain soaks in; more runs off which increases the kinetic energy that washes soil away.

In that canyon I attempted the ecological service of reducing soil erosion. Most of my checkdams failed but one of them had the unintended consequence of splitting a channel of runoff into two smaller flows. An accumulating deposit of sand marked this split where the runoff lost velocity and therefore lost the energy to transport some of the sand and silt it was carrying. I discovered that I could then split each of those channels into two more channels and each of those into two more until all the runoff was observed into the sandy soil of the canyon.

Since then, my hobby for the last thirty years has been to go out in the rain to eroding areas in the West where moisture is Life’s main limiting factor and try to shift downward spirals of erosion to upward spirals of healing and increasing life. Certain principles have emerged from this work. Start high in the drainage where the runoff is just starting to acquire the energy for erosion. If I follow a channel of runoff upstream as it splits into tributaries, I know I will eventually find an opportunity for making a “play”. The play is a place where I can shift some of the runoff onto a slower route. It’s usually a two-step play. First, with my trowel I slice a deeper channel at the shallowest point where some of the runoff is overflowing into the slower channel. That increases the amount of water that can flow that way. Then, second, I take this piece of turf and place it in the main channel in a way that forces more of the runoff into the path I just deepened. (Offer a new path before opposing the old path.) As the runoff splits into two broader channels, it slows which reduces its energy exponentially.

Occasionally I find a place where I can make what feels like a major play but most of my plays appear inconsequential. I can see the diverted water creeping its way down through a more vegetated, absorbent path. I call all of these tiny plays “probabilistic shifts”. None of them create a 100% change in a flow. I can’t predict where a particular water molecule will end up. I’ve just shifted the probability of where it will end up. But I know with mathematical certainty what the overall effect of these changes in probability will be (more of the runoff flowing slower) in the same way a casino knows that the odds set in its favor will lead to money accumulating for the house, despite the occasional big winner. The runoff diverted onto the slower channel will flow slower because some of it will be absorbed by the vegetated soil and cease being runoff and the rest will have to push through resistant vegetation and flow even slower. Meanwhile, the runoff still flowing in the main channel will flow slower because with less volume following the split, the smaller volume of water flows thinner, more subject to adhesive forces slowing its passage.

As my probabilistic shifts accumulate downstream, the surge of runoff is both reduced in volume (because more is absorbed) and spread out through time (because more is slowed down and so converges at a slower rate). Erosive energy is related to both the volume and speed of the water. As the pulse is spread out, the erosive energy subsides with mathematical certainty.

I am changing the rate at which runoff flows so that more soaks in and less soil is moved downslope. Because of this, balances shift and soil and life begin to accumulate in places they couldn’t before. As this happens, they create opportunities for new plays. The work grows on itself. I think of this as allies emerging, creating more possibilities than one can on one’s own.

I am changing the rate at which runoff flows so that more soaks in and less soil is moved downslope. Because of this, balances shift and soil and life begin to accumulate in places they couldn’t before. As this happens, they create opportunities for new plays. The work grows on itself. I think of this as allies emerging, creating more possibilities than one can on one’s own.

One of the key concepts arising out of all of this is “backing up”. When a flow is slowed down, it backs up. When the rock cycle is slowed, it backs up. It flows slower, allowing more time for weathering processes to crack and chip the rocks into smaller fragments with greater surface area which allows the volume of rocks to retain more groundwater which allows more plants to grow among the slow flow of rocks which helps the rock fragments develop into soil that holds more groundwater that can fuel more photosynthesis, more life.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics does not allow things to flow up but it does allow flows to back up. By changing the rates at which things flow, possibilities emerge and accumulate. Ecological awareness comes from seeing how everything around us – mountains, air, soil, whales, food, money, smog, toxic wastes – are the current expressions of rates of flows. Change the rate of a flow and something downstream will change. Nothing is a given. Anything can be changed by changing the rates of the flows that sustain it.

I find that this point of view gives an interesting overarching view of the ecological situation we are in. For example, forests, fossil fuels, soils, groundwater, and high atmospheric oxygen and low carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere are examples of the possibilities that life has banked up over hundreds of millions of years. In the Industrial Age, we have been harvesting this immense bank of possibilities to lift ourselves up. We are ripping through them at an incredibly rapid rate. Many of the ecological crises we face can be understood as the depletion of possibilities – either of the possibilities themselves or of the processes that create those possibilities. So climate change – which focuses on carbon burning/sequestration altering the flow of heat energy within the global system – can also be seen as the burning of possibilities, leaving us with the exhaust waste millions of years of accumulated possibilities. This “rush” has warped our virtues, our sense of why we are here. I teach history to my eighth graders. Each year I try to deepen my historical sense and I keep running into war after war. A tragedy of history is how much of this harvested possibility has been consumed in armaments and short-sighted war, monarchs and emperors trying to expand their territory so they can get a bigger harvest and move higher on the gradient of wealth.

Intermission – Daylength

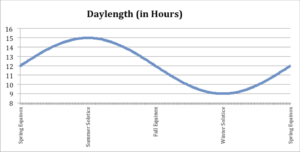

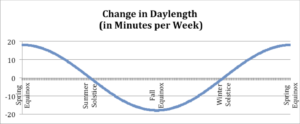

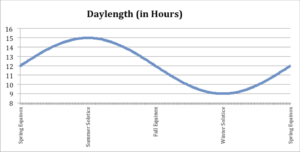

My 8th grade math class graphs how daylength changes through the school year. Each week, we graph that Friday’s daylength. What develops over the months is a sinusoidal curve that drops through 12 hours a day on the autumnal equinox (equi-equal, nox-night) and reaches its lowest point (around 9 hours, 15 minutes for our latitude) on winter solstice and then begins to rise again and crosses the 12 hour mark again on the spring equinox and is still moving up towards its summer solstice high when the school year ends. Kids can relate to this graph. It makes sense with their experience of the shortening and then lengthening day. (For this article, I’m using a graph that extends from Spring Equinox to Spring Equinox.)

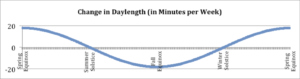

However, each Friday we also calculate how much this Friday’s daylength has changed from the previous Friday’s daylength. We graph that on a graph lined up below the daylength graph. This graph is the mindbender which is why we do it the entire school year so it has time to percolate in slowly.

However, each Friday we also calculate how much this Friday’s daylength has changed from the previous Friday’s daylength. We graph that on a graph lined up below the daylength graph. This graph is the mindbender which is why we do it the entire school year so it has time to percolate in slowly.

These two graphs have a different y-axis. The Daylength graph’s y-axis shows the length of day in minutes. The 12 hour day of Equinox is 720 minutes. (I’ve left off the unused portions of the 24 hour day so the y-axis extends from 9 hours up to 15 hours. If we were above the Arctic Circle, the graph would need to stretch the full distance from 0 to 24 hours.) All the times are positive because all the daylengths are zero or greater.

These two graphs have a different y-axis. The Daylength graph’s y-axis shows the length of day in minutes. The 12 hour day of Equinox is 720 minutes. (I’ve left off the unused portions of the 24 hour day so the y-axis extends from 9 hours up to 15 hours. If we were above the Arctic Circle, the graph would need to stretch the full distance from 0 to 24 hours.) All the times are positive because all the daylengths are zero or greater.

But the Change in Daylength graph is a two-quadrant graph. The y-axis records the change in minutes between each week’s daylength. There is the positive section above for graphing when the days are growing longer but there is also a negative section below for graphing when the days are growing shorter.

The other difference is the scale. The distance from the bottom to the top of the first Daylength graph (9 hours to 15 hours) is 6 hours while the distance from the bottom to the top of the second Change in Daylength graph (-20 minutes to +20 minutes) is only 40 minutes. So the bottom graph is bringing out something smaller, more subtle. (If we were using Sunrise/Sunset times that were accurate to the second, the Change in Daylength graph would appear smooth like the Daylength graph but since we are using times just to the minute, there is a bit of “chatter” in the graph.)

It takes several months of weekly graphing for these two graphs to “fit together” in my 8th graders’ minds so if this is new stuff for you, you might have to reread this section over a couple of times.

Both graphs are sinusoidal wave graphs. However, the Change in Daylength graph is offset a quarter of a year ahead of the Daylength graph. This is easiest to see with the lowest point on the graphs. The lowest point in the Daylength graph is Winter Solstice but in the Change in Daylength graph, the low point has shifted over to Fall Equinox.

The quarter-year offset between the two graphs is easiest to understand for the shortest and longest days of the year. The shortest day of the year, December 21st, is the shortest day of the year. The day before is not quite as short so the change in daylength is going to decrease from the day before to the shortest day of the year. The day following the shortest day of the year can’t be shorter. It is a bit longer so the change in daylength is going to increase. So the shortest day of the year is the day when change in daylength shifts from growing shorter to growing longer. On the Change in Daylength graph, this has to be where the line crosses up through the Zero Line from the negative half of the graph to the positive half of the graph. So when the Daylength graph is at its lowest point, the Change in Daylength has to be at its midpoint.

The same logic applies to the longest day of the year. Because the longest day of the year is the longest day of the year, it has to be the day where lengthening days changes to shortening days which means the Change in Daylength graph must cross down through the Zero Line on the longest day – precisely because it is the longest day.

Once you understand these two points, then you can understand why the two graphs are shifted with the peak in Daylength coming 1⁄4 of a year after the peak in Change in Daylength. Then one can start to understand the dynamics of why the two equinoxes (when day and night are balanced) are the times of greatest change in daylength. In November, when the Daylength graph is moving down, the Change in Daylength graph is moving up. Why? How can this be? And in May, when the Daylength graph is moving up, the Change in Daylength graph is moving down. Why? How can this be? As Lane, one of my students once famously explained in May, “The daylength is growing longer shorterly.”

End of Intermission

How do we change the downward direction of our

planet’s thermodynamic velocity upwards?

What does physics have to say about changing direction?

One of the first things Sir Isaac Newton would say is that an object in motion will continue in that motion unless acted upon by some force. If we want to change our direction, we will need to apply “force”. What does that mean? What does physics say about force?

One of the first things Sir Isaac Newton would say is that an object in motion will continue in that motion unless acted upon by some force. If we want to change our direction, we will need to apply “force”. What does that mean? What does physics say about force?

The physics of force starts with a “body” at a certain position at one time and then, after a certain period of time, that body is now in a different position. The change between those two positions is a change of distance in a certain direction. If that change in distance is divided by the amount of time required for that change, the result is velocity. (A car that two hours later had moved 100 miles to the east would have a velocity of 50 mph to the east.)

One of the things that my introductory physics class hammered into us over and over again is that velocity is not the same thing as speed. Speed is like 60 mph. But velocity is both speed and direction. 60 mph to the east is different than 60 mph to the west. One needs to always remember these two different aspects of velocity. For example, if we want to change a car moving 60 mph south to 60 mph to the east, we don’t have to bring the car to a stop, turn it 90a, and then accelerate it back up to 60 mph. We just have to turn the wheels of the moving car until we are going east. The car wheels are exerting a force against the ground to turn the car but it is a more manageable force than one might first realize. So when we wonder how to change the direction of our culture, we don’t necessarily have to slow down or stop the momentum; we just have to turn it.

One of the things that my introductory physics class hammered into us over and over again is that velocity is not the same thing as speed. Speed is like 60 mph. But velocity is both speed and direction. 60 mph to the east is different than 60 mph to the west. One needs to always remember these two different aspects of velocity. For example, if we want to change a car moving 60 mph south to 60 mph to the east, we don’t have to bring the car to a stop, turn it 90a, and then accelerate it back up to 60 mph. We just have to turn the wheels of the moving car until we are going east. The car wheels are exerting a force against the ground to turn the car but it is a more manageable force than one might first realize. So when we wonder how to change the direction of our culture, we don’t necessarily have to slow down or stop the momentum; we just have to turn it.

Again, one of the acknowledged “stretches” in my metaphysics is applying the physics of velocity of objects to something I call the “thermodynamic velocity” of our culture or our planet.

The most effective way to change the direction of something with whatever force you have is to apply your force perpendicular to that thing’s current velocity. So often we get so focused on resisting, opposing, stopping that we forget about the possibility of turning something. That was one of the first lessons working with the runoff taught me. I tried to stop the runoff with checkdams but they held back only a tiny percent of the total flow. Once the checkdam overflows, the water’s energy is concentrated upon the plunge pool at the downstream base of the dam, undercutting the dam. Trying to oppose the flow did not work. But splitting the water, in effect turning some of it onto a new path, had more effect than I would ever have imagined because it reduces the kinetic energy of all the water flowing past the split. My limited force was more effective in slowing the runoff.

In addition, this strategy can lead to a fascinating dance because it is the recipe for a feedback spiral and in that dance lies power to sustain change. You want to change the direction of something, so you apply your force perpendicular to that direction. This will nudge the angle of that thing’s velocity slightly which now changes the direction that is perpendicular to this new direction. As the thing’s direction changes, one keeps changing the direction of one’s force to be perpendicular to that new direction which keeps nudging the object’s velocity ever more towards the desired direction. This feedback between direction of velocity and force applied perpendicular to it can get very curvy and swoopy like a good dance. A sustained series of small applications of force to the direction of an object or a flow can result in a change of direction without having to exert great force at any particular point.

The second thing that Sir Isaac Newton would say about changing direction is F=ma, force equals mass times acceleration.

Acceleration is any change in velocity. Acceleration is interesting because it exists within a mathematical cascade deriving from position. An object begins at some initial position. If it moves to a different position, then this change of position is of a certain distance in a certain direction in a certain time. These three aspects of the change in position determine its velocity. What if we want to change the direction of that velocity? Since direction is part of velocity, a change in direction is a change in velocity which means that this change is an acceleration and will, by Newton’s Second Law of Motion, require Force. Force, the ability to change the universe, operates at the level of acceleration, at the level of changes in velocity.

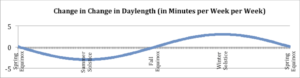

So Acceleration, the change in Velocity, has the same mathematical relationship to Velocity as the the Change in Daylength graph has to the Daylength graph. (Mathematically, the “change in” graphs are both graphs of the slopes of the other graphs.) And for the same reason, a velocity graph that oscillates will follow a quarter cycle behind an acceleration graph just as the Daylength graph will lag the Change in Daylength graph by a quarter year. This time lag of a quarter cycle is hard to understand. It creates a confusing time lag between the cause of accelerating force and the effect of velocity. This confusing time lag is important to be aware of if we are trying to change the direction of something.

I once saw this lag between cause and effect in a memorable way. My class was walking back to school down the gentle grade of a newly-paved, not- yet-open-to-traffic road. Two of the oldest boys asked if they could try to roll down that gentle grade while sitting on a skateboard. So, like kids on a sled, one sat behind the other and they started rolling along at little more than walking speed.

They started out fine but their combined weight was not quite centered so they started to veer to the left. This led them to lean to the right which brought them back around until they were going to the right but now they were swerving towards the right so they leaned more strongly to the left which brought them around too quickly so they leaned again to the right and rolled off the skateboard onto the pavement. I remember this well because they tried four or five times and every time the same slow motion rolling off onto the pavement inevitably happened. It all happened slowly enough that I could empathically feel the shifting of weights and the swerving growing out of control. Over and over again. There was something out of balance that they couldn’t get right. What was it? They weren’t turning out of their turn soon enough. Each swerve inspired a greater shift in weight from them that was harder to shift back in the other direction in time to avoid the next swerve.

Here’s an image to help think about these time lags: Why is it that when we are steering a car around a tight turn to the right, we start turning the wheel back to the left halfway through the turn?

If we kept the wheels turned all the way to the right until the car heading in the direction we wanted, then the car would still be turning further to the right and by the time we had straightened the wheels, the car would be heading off to the right of where we intended to go. We would have to then swerve back towards the left. One of the marks of my beginning driving was my car swaying back and forth within my lane. The car will oscillate back and forth until we learn to start turning away from our goal before reaching it.

Learning to navigate the time lag between the turning of the wheel (cause) and the turning of the car (effect) is part of a fundamental challenge of life. Learning to turn away from one’s goal before reaching it is paradoxically confusing. One needs to have a clear image of what direction one really wants to go so that one knows when to start turning out of the turn. This challenge of life grows harder if it involves many people because different people have different ideas of where they want to go. Expand the number of people into a culture and the time lag can lead to a history of cultural swerves and crashes that requires thousands of years of communication to finally figure out.

Those two boys on the skateboard have become my image of humanity over thousands of years crashing ecosystems and empires over and over again. There is something hard to understand, learn, master. They couldn’t learn the dynamics of the time lag in order to start turning back before they reached their goal of heading straight down the road.

That is the great danger of the gradient of wealth. When you are in competition with others to be the one at the front of the line, there never comes a time when you can turn back before reaching your goal because if you do, the competition will catch up and pass you. Those racing for position in the gradient of wealth are locked in; they can’t turn away on their own. Unfortunately, the gradient of wealth concentrates political power on those who are most resistant to changing direction.

Historically, these people tend to use this power in three ways. They use it to privatize the commons and harvest its ecological services. Their wealth (and hence power) grows from doing this, but they are altering the rates of flows that shape the land and culture so that a lot of things once taken for granted start to flow away. Soil. Drinking water. Coastlines. Glaciers. Belief in the economic value of higher education. Faith in one’s government. Hope. Less becomes possible within the larger culture.

The second thing they do with their power is to insulate themselves from these growing consequences. Bottled water is cheap for them and actually presents an investment opportunity as poorer people lose access to local drinking water. Gated communities and private security firms insulate one from the growing consequences of one’s actions in the pursuit of wealth. They don’t feel the full force of the Earth giving the feedback to change direction. Thinking this resistant feedback is a cost, they externalize it on to others.

The third thing they do with their power is to try buying off or suppressing the feedback that is increasingly shouting to turn the wheel back. Suppress information showing a link between smoking and cancer. Cast doubt on climate science. Suppress information on football-related brain trauma. Those caught up in climbing the gradient of wealth don’t want to “turn the wheel back” because they are not navigating by a direction; they are navigating by position – their position in relation to others in terms of “acquiring more wealth than others”. Therefore, we need to realize that our “leaders” will not lead the culture to turn out of the curve. They will be some of the last; they will be the followers in this regard. It’s just part of the structure of the gradient of wealth. Realizing that the force to change our culture’s direction must come from elsewhere is a step in absorbing more of our own power, not letting it flow away to “leaders.”

What the fields have taught me is that the wise direction to steer by is “creating more wealth within the entire system”. It’s the difference between the left graph and the right graph.

The goal is not to ride the steepest rising arrow possible for oneself. The goal is to do the work of helping the entire planetary system move in a direction that is upward, even if only slightly, so that possibilities can begin to accumulate.

Another way of thinking of this is the difference between “up” and “upward”. To live within increasing possibilities is a reassuring and pleasant experience. The faster the possibilities increase, the more fun becomes the experience. One can seek “up” at an increasing rate. But if the “up” comes through harvesting the greater system at a rate that is decreasing its possibilities, then the experience of “up” becomes tainted; one has to draw a curtain around oneself so as to not see how one is decreasing possibilities in the surrounding world. One has to build walls around you to fend off the growing resistance and hostility.

Instead of swerving off into unlimited personal gain, wisdom lies in turning the wheel back earlier so that finds a balance between personal gain and systemic gain as one heads in the direction of helping the largest system increase in possibilities. One uses the energy one has harvested from others to do the ecological/cultural/interpersonal service that helps increase possibilities in the world around one.

Another way of thinking of these two paths is the contrast between a gully and mats of moss up at timberline. A gully converges runoff upon itself so that it has far more water flowing through it than the surrounding land. That water erodes the gully deeper which allows it to pull more of the runoff towards it ever stronger while depleting the surround land of possibilities. On the other hand, a mat of moss up at timberline that has access to flowing snowmelt grows faster, pushing itself higher. This redirects some of the flowing water to the lower areas around that mat. In effect, the successful mat of moss gives the gift of water to other mats of moss lower than itself. They can now grow thicker, taller and when they overtop the original mat of moss, they will give the gift of water back to it. Help others rise and then they will pull you up as they rise and evermore of the gift of water will be held in place, transpired, and recycled. On this path, one surrounds oneself with allies.

The wise culture navigates by “More possibilities within the entire system” rather than “More possibilities for me.” This idea began forming as I did my erosion work up in the fields. I decided then to try making my life an experiment of this idea. When I wrote Shifting, I gave it away free to forty people, asking them to pass it on and I ended up selling 1500 copies plus having Chelsea Green publish it as Seeing Nature of which I sold another 1000 copies. I didn’t make much but I wasn’t doing it for the money; I was doing it to try spreading ideas I thought could help. I’ve done the same thing with Cairns. No charge. No advertising; just wanting to help my culture steer a wiser course.

Alysia, as an ambassador for teacher-powered schools, talks with other teachers who want to transform their school or create a new one. There are many obstacles they must overcome. One of the biggest is the need to earn a salary during the school’s uncertain start-up. Alysia and I realize we got around this obstacle because we had decided earlier to live on my one modest income so that Alysia could be home with our young children. This allowed us to start Chrysalis as a home-school program where Alysia was teaching our children and three other children for free. This allowed Chrysalis to grow to where, in the second year, she could earn a salary and still be with our kids.

Almost every day, I feel the blessing Chrysalis has created in my life. To watch children come into Chrysalis with damaged spirits at half-mast and watch their light grow stronger and know you are part of this process of healing spreading through a culture into new families is such a blessing. It’s a blessing not in a loud rah-rah way but in a quiet sense of enough-ness and a grounded sense of hope. (Last week, Chrysalis celebrated our 20th year with a reunion gala. It was an uplifting rush for Alysia and I to talk for three hours with families who were saying Thank You and knowing that the Thank You’s were genuine and deserved.) All those involved with Chrysalis are not getting rich. We keep putting the kids first, choosing small class sizes over large salaries. You can buy stuff with money but being part of something that grows the world upward is a whole different category of possession.

This personal experience leads me to think of “income inequality” as an example of turning rather than opposing. It should not be framed as an us vs. them issue. Where we want to go does not pit poor against rich. We want to go towards greater possibilities and hope for all. It’s not taking from one group to give to another. Instead, it is probabilistic shifts in the flow of money so that it converges more slowly, has more opportunity to recycle within the community. One’s intent in this regard is important because when it comes to politics and rule-making, the regulations can be seen (and will definitely be perceived by some) as an attempt to harvest others for the benefit of my group. If it has this spirit, it can contribute to the “running for the bus” escalation that spirals downwards.

Instead, we should turn our focus from money as an object to wealth as a flow. What are the sources of our wealth? Natural resources are major sources. Fresh water, fertile soil, petroleum, minerals, trees and the inflow of solar energy. Human skills and creativity are another source of our wealth. A wise culture holds these flows of wealth high on the slopes where they can soak in to nourish structures that can recycle the flows over and over again, so that the soil grows deeper, the fresh rains increase, the human spirit grows hopeful.

The main problem with income inequality is that, like a gully system channeling rain out of a watershed before it has a chance to soak in, it drains creative hope out of the culture and turns people against one another in struggles for limited resources. The highest rates of return are found in short- term arbitrage so rather than soaking in high on the slopes to nourish cultural wealth, huge reservoirs of capital slosh in and out of countries and economies, destabilizing them and creating further arbitrage opportunities. This direction reduces creative hope – and creative hope is one of the sources of a culture’s wealth. A wise culture inspires people to focus on creating more wealth rather than gathering more wealth than others. Gathering more wealth than others is what the gradient of wealth nourishes and as wealth concentrates, it turns into the political power to concentrate wealth even further at the expense of the culture until the system dwindles away. Will we swerve and crash empires once again on a global scale or will we finally have a sense of direction that helps us learn to start turning out of the curve earlier than we’ve tried before?

(I do not wish to imply that the only challenge facing us is income inequality. Human population density exacerbates every other challenge we face. The loss of pre-scientific explanations that anchored many cultural wisdoms has left many spiritually adrift and allowed the gradient of wealth to assume a larger meaning in our lives.)

Intent

My kayak has a foot-operated rudder which I love using. My foot applies force against a pedal which, through a cable, holds the rudder in a certain position which then exerts a force against the water we are gliding through. Depending on the rudder’s position, the force of my foot is holding the kayak on course or turning the kayak. My eyes and body can detect how the kayak is moving. My mind is assessing whether this movement is what I am wanting. my eyes, mind and foot are dancing with the rudder, kayak, wind, and current in an oscillating glide through the water (in the same way my students’ eyes, mind, and hands dance with the poles they practice balancing on their hands.)

As I do this steering dance, I think of the levels. There is the level of position that I am constantly paying attention to and how it changes which is its velocity. I am constantly changing that by adjusting the force of my feet on the rudder pedals. That force through the rudder changes the direction of the kayak, which is a change in velocity, which is acceleration. That is third level down. Position, then velocity, then acceleration. But there is another level below that because my mind is constantly assessing whether this force is accurate and changing the force that my feet are exerting. This changes the direction of the force, the direction of the acceleration. That is a “change in acceleration”, which is the next level below acceleration.

Classical mechanics starts with position. Change in position is velocity. Change in velocity is acceleration. But change in acceleration is …? My introductory physics class never mentioned this. On the internet I learn that “change in acceleration” is called “jerk.” As I kayak, I find this level below acceleration fascinatingly potent. It’s the level where feedback from the boat’s direction is flowing through my mind to adjust the force of my feet. In my metaphysics, I think of this, not as Jerk, but as Intent. It’s the level where one starts to turn out of the curve before reaching one’s goal in order to go the direction one wants. It’s the level where the shift from “gaining more wealth than others” to “creating more wealth for all” happens, where the shift from “The world is doomed to run down” to “Upward is possible” happens.

The same quarter cycle shift happens when we drop to the level of Intent as happened when we dropped from velocity down to acceleration. This adds up a half cycle shift between what we see on the surface and what is currently changing future dynamics. One level is opposite of the other. (On the next page, I show the two Daylength graphs again with a third one added to show how each level adds a quarter cycle shift.) We need to learn to navigate this very large, confusing shift just like those kids needed to learn to navigate their skateboard.

One result of this half cycle shift is that if one is successfully acting at this level of intent to turn a downward velocity back upwards, the situation will always get worse first because the growing worse has to slow down before it can reverse. As it is slowing down, the situation continues to grow worse. Another implication of this is that one can’t wait until the last minute to try reversing a situation. Far wiser to start acting on the new intent much earlier than that.

It’s easy to get confused by which level to navigate by. We are tempted to steer by the uppermost level of position (and we are immersed in advertising that tries to focus our attention almost exclusively on that) but change happens several levels down and can be moving in opposite directions. (I often think that the dynamics of all these different levels moving in different directions might be the taproot of the wisdom within the ancient I Ching – advice for how to live a straight life amidst the confusion of these levels.)

If we don’t understand the quarter and half-cycle shifts, we make the mistake of looking to the glory days of an empire for inspiration. We like our houses to have white pillars like classical Greek and Rome at their peak but by then, the rot was setting in. The virtues in history are not associated with cultural peaks. The virtues are more humble and earlier in the cycle. Steer by those.

This idea of steering is central to this essay because this is what we are trying to do, trying to steer an upwards course into the future. So when I am kayaking, there is a constant shifting back and forth of my feet against the rudder pedal, a constant change in force, an oscillation in acceleration and all the levels of velocity and position arising from that. They are all bound together in a dynamic equilibrium between what is actually happening and my intent.

Similarly, as a naturalist, I see the world as dynamic equilibriums of relative balances of underlying flows. Oscillations driven by balancing feedback spirals characterize dynamic equilibriums. (The classic image of oscillations is created by young children when they pretend to drive a car. Their hands turn an imaginary steering wheel back and forth.) The system, starting to move too far in one direction generates counteracting forces that swing it back in the other direction which then generates other counteracting forces to swing it back the other way. It’s the oscillations back and forth that make the equilibrium dynamic, that keep the feedback spirals swerving the shaping forces back and forth. There are already underlying forces pushing dynamic equilibriums towards the direction we wish to steer. We can change directions by altering the flows that underlie the current dynamic equilbrium. Reduce some forces, increase others. There are a series of turning points (inflection points) at the lower levels that one can navigate by to sustain hope during the period in which things are getting worse before change is detectable.

I’ll close with my memory of learning to ride a bike. Dad would hold the bike as I got on and then push and steady the bike as I started to pedal. He could keep up for only a few steps into this process. As I pulled away beyond his steadying hand, I would crash. Over and over again. And then one time, I told him to let go but I didn’t feel him let go so I glanced back to discover he had let go long ago. I promptly crashed. But the next time, I kept on pedaling and that was it. I had somehow learned the fundamental lesson of how to ride a bike. There was no intellectual “aha” moment preceding this. One time, it just happened; my mind/body had learned it and it never forgot.

This memory is one reason I remain hopeful no matter how dire the news from the world becomes. Humanity has crashed so many times in so many horrible, tragic ways. Some complex lesson of balance have eluded us for so many thousands of years that we can slip into an assumption that we are doomed to crash again. But maybe we are on the verge of learning how to ride the bike of civilization and this time we won’t crash but instead keep on pedaling and ride off into a whole new, empowered phase of history. This is the hope that underlies this article.

Deep appreciation for your courage and wisdom. You are an inspiration.